The quest to find materials which safely store large amounts of hydrogen has received a tantalising boost. US chemists have announced the discovery of a new hydrogen-storage material, which they say stores large amounts of the gas at room temperature. The material is nowhere near practical application, but its theoretical capacity beats oft-quoted US Department of Energy targets for storage materials to power a car several hundred miles on hydrogen fuel.

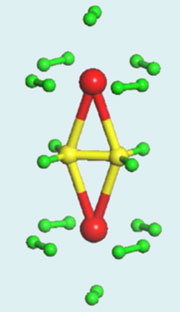

Ten hydrogen molecules (green) surround a capsule-like ethylene molecule (yellow) attached to two titanium atoms (red).

© © Tanir Yildirim, NIST

|

Bellave Shivaram and Adam Phillips, of the University of Virginia, announced their findings on 12 November at the International Symposium on Materials Issues in a Hydrogen Economy, held in Richmond, Virginia. Titanium molecules complexed with ethylene, and bound to an inert support, created a thin film which strongly absorbed up to 14 per cent hydrogen by weight at room temperature. Most materials today absorb 7 to 8 per cent of hydrogen by weight, and that only at very low temperatures.

Last year, physicists led by Taner Yildirim working at the US National Institute of Standards & Technology (NIST), Maryland, predicted that transition metal atoms bound to ethylene could bind large numbers of hydrogen molecules.1 As they explained, the interaction between hydrogen molecules and transition metals is just strong enough to allow binding around room temperature.

The key to experimental verification, Shivaram said, was to prevent the titanium-ethylene complexes from clustering together on the support, so that hydrogen molecules could fit between them. This means that for practical hydrogen storage the molecules would have to coat the surfaces of sponge-like supports with high internal surface area, such as zeolites - and that, together with low-purity hydrogen gas streams, could reduce the total weight per cent absorption of the whole system.

Shivaram said that the findings, which are unpublished, met with some scepticism at the symposium. They have not yet been separately validated, as the system is not robust enough to be sent out from the lab. Nor have the researchers done experiments to check whether hydrogen can be released and re-absorbed in cycles, though theoretical predictions suggest this could be possible.

But the inventors are working to patent their discovery, and are hopeful that they will be able to steer through the many pitfalls that could scupper the system. 'In terms of hydrogen absorption, these materials could prove a world record,' said Phillips.

Richard Van Noorden